Vendors’ carts and awnings line the street across from Florence’s Basilica San Lorenzo. Photo by Roy Scarbrough

The three bouquets someone attached to the barricades could stand as funerary offerings for the once-lively and historic marketplace. The city of Florence has cast out the money and souvenir exchangers from the vicinity of San Lorenzo Basilica steps.

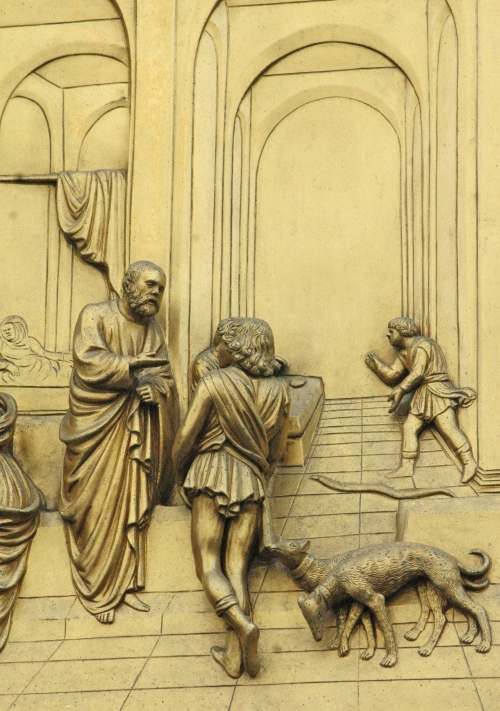

Not everyone is sorry that the street merchants of the San Lorenzo Market have folded up their canvas awnings and wheeled their push carts away. Some folks are happy with the newly unobstructed views of one of the city’s principal Renaissance-era structures, Basilica San Lorenzo. The news has not been good for the vendors who have long operated a kind of flea market around the church. The city has now ordered them out.

Officially, the move is temporary. The city needs to reset the paving stones in the street and in the plaza as part of a redevelopment plan for the district. These things take time, a lot of time in Italy. There’s no guarantee that vendors will be back, and even the mayor is talking like merchants are gone for good.

The marketplace has its own cultural history. The vendors have been saying they have been in the piazza since 1792. That was barely twenty years after workers completed the finishing touches on the church.

In the decades that poets Robert and Elizabeth Browning lived in Florence, Robert liked to browse through the old books in the market. In 1860, at one of the vendor’s stalls, Browning found a bound volume of official trial court records of the 1698 Franceschini murder case. This was a sordid affair involving a count who killed his unfaithful wife and in-laws, a story that became the basis of Robert’s best selling book, a long narrative poem, The Ring and the Book.

A tweet from Mayor Matteo Renzi last week shows the extent that some people welcome the ouster of the street merchants. “Basilica di San Lorenzo libertata dalle bancarelle'” the Mayor Tweeted. That is, “Basilica San Lorenzo now liberated from the cart vendors. We have liberated as promised the San Lorenzo area. One of the most beautiful places in the world. ” You’d expect that there was similar sentiments expressed over the end of the French occupation of 1494.

A quick check of more #Firenze tweets shows some solidarity with the popular mayor. “What a beautiful sunny day it is in Florence. San Lorenzo without the push carts.” says another Italian language tweet.

Personally, I’ve enjoyed the buzz of the place. I’ve watched the vendors in the mornings wheel their carts to the lanes surrounding the old church and its cloisters, then spread their white canvas awnings. And I’ve watched these fellows push their rigs home, down dark, half-lit, narrow streets at night, the wheels rattling over the paving stones. The selfie I use for my Twitter avatar happens to be a picture I took while standing front of a cracked full-length mirror that one of the vendors had set out for his customers. So, there was something there that was part of my identity.

I’ve always found the vendors convivial. On the final day of my last visit to Florence, I bought two men’s wool scarves. He told me his name is Eddie. I’m guessing it was really, Eduardo, but he wanted me to know him as Eddie. I liked him, and it seemed like he liked me. Eddie taught me how to tie them in the traditional Florentine fashion. When it came time to pay, I was short of Euro. I tell I’ll come back for my purchase after visiting the ATM. He says, no, take them now. You come back and pay me.”

Over the years I’ve purchased two Chinese-made wallets. Functional wallets with a built-in coin purse in a style I think I might now have to have custom made. I’ve bought maybe three Italian-made woolen neck scarves, and a pair of sandals from an Italian manufacturer that claimed on its tag to supply the pope with footwear.

To be fair, none of these things I’ve purchased in the San Lorenzo market were produced by local craftsmen, which is part of the public’s complaint against these vendors. While the marketplace has historic roots, its critics see it as lacking in complete authenticity. Robert Browning was English and the 17th Century murder trial documents he purchased came from Rome. Fair enough. Still, there’s stuff there that people who live in the neighborhood can use. As far as I know, the San Lorenzo Market commotion never woke the Medici dead, and its reputed tackiness has never made any of them roll over in their tombs across the street.

So what’s the big picture? Change happens. People adjust. Across town, for hundreds of years, butchers and tanners occupied the shops on the Ponte Vecchio. Their time to go came one day in 1593 when they were replaced by the goldsmiths on order of Duke Fernando de Medici, who disliked the odors from those establishments.

Who now misses the butchers? Not many, but I think I would like to see them at work when crossing the Arno. The jewelry I see in the Ponte Vecchio windows doesn’t interest me so much. When I see all the gold, and the high-Euro price tags, I try to remember the tanners and butchers.